Jigsaws have enjoyed a resurgence, thanks to #stayhome. Apparently even Hugh Jackman is a fan, so we’re in good company!

I’ve always enjoyed jigsaws. In the mid 1980s, when I was 17, a car accident saw me in hospital for two weeks. There was no such thing as a television or radio for every bed. No mobile phones or tablets – just a common room where you could watch TV, play board games or do jigsaws. My mum and I whiled away many hours working on jigsaws.

The most challenging was the jigsaw in a picture-less box! We worked it out in the end.

My autistic daughter has inherited my love of jigsaws. But she has her own unique way of doing them, and it has literally taken me years to figure it out.

Over time, she progressed beyond the small woodblock and inset puzzles, to the cardboard puzzles of 50-100 pieces. However, her modus operandi of putting these together often perplexed me.

First, she’d count out every piece multiple times, and put them into small piles. Okay, not necessarily that unusual.

Then, she’d do the same puzzle over and over again. Yes, also not unusual, particularly for someone with autism.

It was her last strategy that I really found hard to understand. She never looked at the picture when working out where the pieces went.

To me, this was nuts. How could you possibly work out where a piece fitted if you had no idea where its colours or patterns belonged in the “big picture”, so to speak?

Moving onto a new puzzle was almost impossible. She’d do one over and over and over until at last, I’d resort to hiding it so she could learn to do a new one. Gradually, slowly, over years, she extended her jigsaw puzzle range. Often, I’d start the new puzzle, then she’d take over, and the new one would become the current favourite.

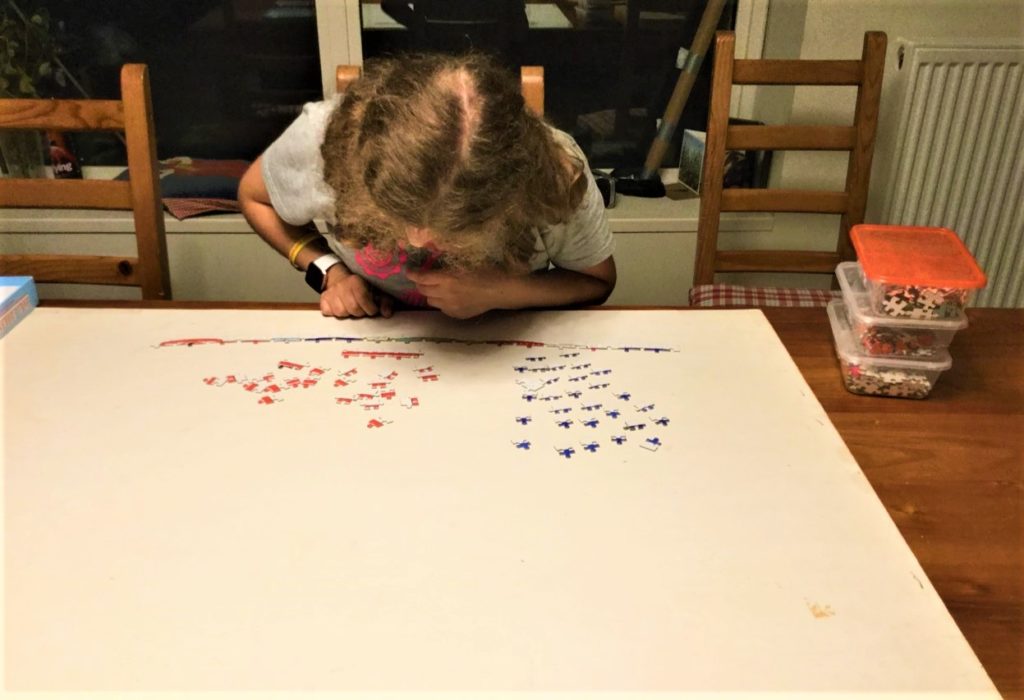

She would still count every piece and put them into piles. This meant that doing puzzles seemed to take an inordinately long time, especially as she progressed to the 500-piece puzzles. However, I did start to notice that she seemed to be familiar with every piece in a puzzle, and would lay them out in order, like a brickie laying bricks.

It was quite extraordinary to watch.

This realisation only struck me when I noticed one day that the puzzle was being filled in in a very regular way – not the way I usually worked, which was more of a “cluster” approach, matching easily identifiable pieces of the puzzle. I was amazed and impressed, but wondered whether her approach would let her do larger puzzles.

Surely, I thought, you still needed to be able to look at the big picture, not just the micro detail?

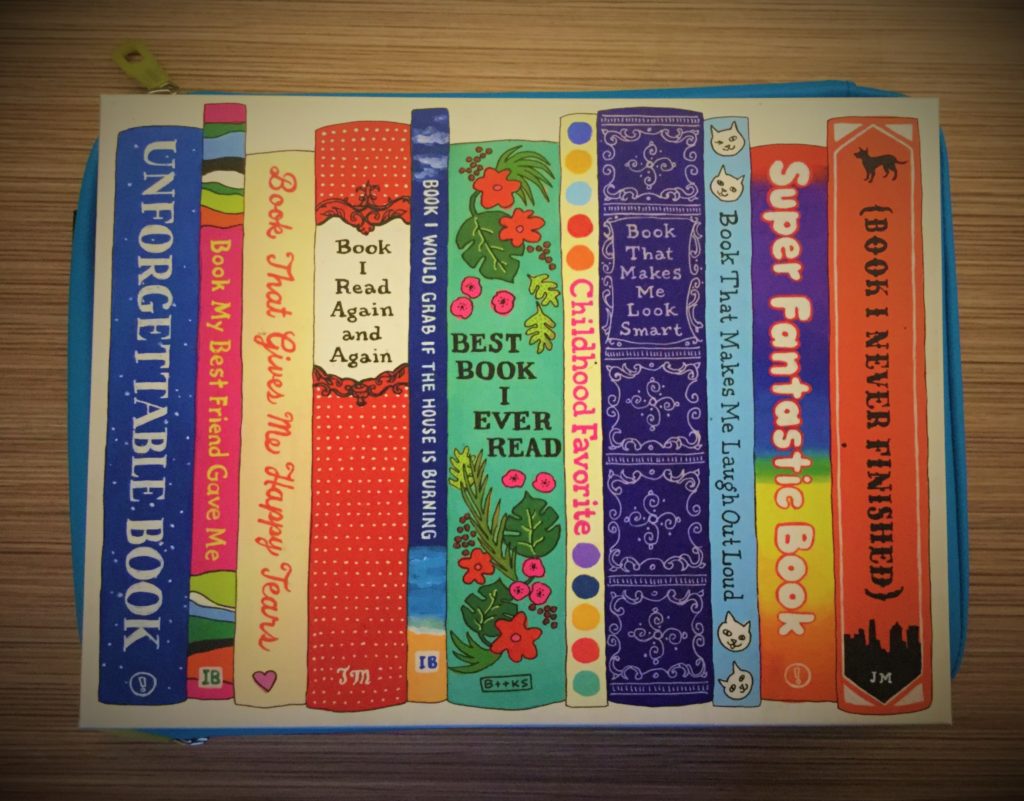

A couple of years ago, my husband and I found a brilliant jigsaw puzzle of a row of books. We thought it would suit her perfectly.* This puzzle was next level at 1000 pieces, twice the size of her (then) 500-piece favourite. However, the pictures were very clear. Each book had a distinctive colour, pattern and lettering. Even if she didn’t look at the big picture, it would be relatively easy for her to sort out the puzzle’s different sections.

Despite this, it was the usual slow introduction to something new. However, she eventually got into it, and the “books puzzle” became her new favourite.

She currently has three favourites: a 500-, 1000- and 1,500-piece puzzle. I’m working around to introducing another to join the favourites list. A birthday gift from one of her uncles, it has been languishing in her bedroom for two years. As I mentioned, it’s a slow process!

Anyway, I started to notice more of a pattern to how my daughter did things.

The piles of pieces that she held were ordered so she could lay pieces out sequentially. She’d count them into a pile in her hand, which would be stretched to the max, then place them precisely – almost rhythmically – in order. Counting them meant she knew exactly whether she had all the required pieces or whether some were missing.

I swear, she knew every piece by heart. You know, when you do a puzzle, that often a few pieces stick in your mind for some reason – an unusual shape or pattern, or a distinctive colour. There’s no way I would every know every piece on a puzzle – not even if I had done it many times.

Not so my daughter.

Just because I don’t understand the purpose, doesn’t mean there isn’t one.

She’s discovered a way that works for her. Who knows? Perhaps she’d already imprinted the picture into her memory so she didn’t need to keep referring to it. She has a great eye for detail, and an amazing memory. Those are two of her “superpowers”. Knowing all the pieces means she can order them the way she wants. The constant counting and pile-making which used to so distress me (because yes, I didn’t understand why she was doing it and it seemed utterly pointless) is absolutely essential to the way she works on puzzles.

It’s still really hard to introduce her to a new jigsaw. Her superpowers do rather stand in the way of this! Nevertheless, even though it can take weeks, if not months, to introduce a new puzzle – especially as they get larger – she does get there in the end. Her current three favourites were all new once.

It’s a team effort. If I didn’t push the point (admittedly, this does still require hiding the current favourite), she wouldn’t stretch what she can do.

Working out the puzzle from the jigsaw and what really matters

Am I right to do this? You’ll have your own views.

I strongly believe in challenging my daughter to help her grow and develop her strengths, and to learn ways of adapting to or working around her weaknesses. The more aware we are of her weaknesses, the more we can provide appropriate supports.

This isn’t about making her into someone she’s not.

It’s about embracing, enhancing and extending what she’s good at, helping her work on the tough stuff and supporting her however and whenever necessary.

I’m in awe of the way my daughter completes her puzzles. I’m still frustrated it’s such a process to introduce her to a new one, but in the grand scheme of things, does that matter?

It’s hard working with anyone who has an intellectual disability and difficulty communicating. It’s especially challenging for both sides when you don’t understand the purpose behind something they’re doing which seems purposeless. I love my daughter to bits, but it doesn’t magically take the challenges away.

What this experience reinforces for me is that just because I don’t understand the purpose, doesn’t mean there isn’t one. And maybe it’s not up to me to judge whether or not that purpose is useful. I guess that depends on the context. But it’s a challenging reminder to me to look outside my own frame of reference. If my daughter has found, by herself, a method that works for her, that’s brilliant. And I need to support that.

I’m in awe of the way my daughter completes her puzzles. Yes, I’m still frustrated that it’s such a process to introduce her to a new one, because I can see how thrilled she is when she has mastered a new puzzle.

But really, in the grand scheme of things, does that matter? Of course not!

So enjoy your puzzles in “iso” – whether jigsaw puzzles or the puzzle of how your child’s mind works. And may you find joy and fulfilment in both.

Until next time, stay safe, soap on and Happy Wombatting!

* The jigsaw is called “Ideal Bookshelf”, designed by US artist Jane Mount, who fashions pieces for people who love books!

Ideal Bookshelf is a 1000-piece puzzle by Galison, available through Booktopia and other retailers.