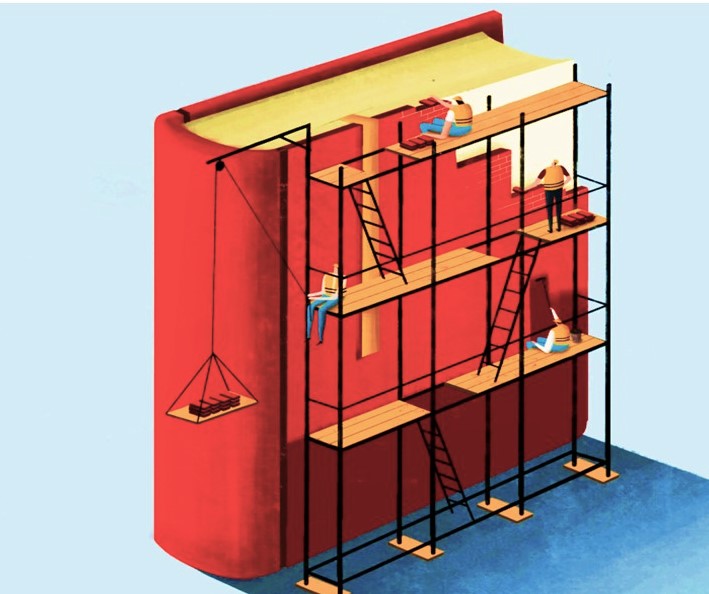

Scaffolding supports things, including you and me

We’ve all walked past scaffolding. Those skeletons of poles and platforms positioned around buildings to support their construction (and protect us), then gradually removed as they’re no longer needed.

When you go about your daily routines of helping your dependents learn, relearn and extend their life skills and tasks, I bet you don’t call it “scaffolding”. But that’s exactly what you’re doing.

Teachers often talk about scaffolding for learning. They try to provide the right supports for students so they can ultimately manage tasks and live independently.

These supports get structured in all kinds of ways. It might be physical. Or it might be less tangible, like breaking down a task into its constituent elements.

When you care for someone, you instinctively understand exactly what you’re doing and why. For example, you know you probably won’t be holding the kids’ hands forever, or helping them with their homework. But you instinctively understand that your help is a vital step in their progress to becoming independent walkers and learners.

Sometimes our charges want extra support even when we know they’re perfectly capable of doing whatever we asked them to do. But it’s moral support they seek.

My daughter often asks for help when she doesn’t really need it. For instance, pouring a drink from a full bottle of milk. It helps her feel secure, or boosts her confidence if she’s tentative.

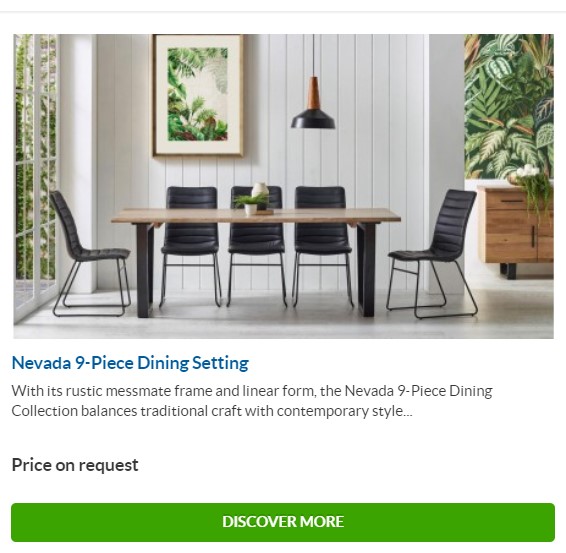

“You have $200 to spend at Bunnings”. Seems a simple enough task, doesn’t it. But making choices can be agonising for autistic people.

But sometimes there’s no scaffolding.

If that were a building, you can picture it collapsing and people getting injured, even killed.

While stuff happens all the time with buildings, at least we expect to see scaffolding and supports. Entire businesses specialise in it. Yet when it comes to people, lack of time and lack of patience can all lead to supports being withdrawn or simply not provided in the first place. I won’t be the first exasperated carer who’s called out “I’m busy! Can’t you just do it yourself?”.

Sometimes, too, we don’t provide scaffolding because we haven’t really grasped the immensity of the task we’ve set for someone.

I have a specific example in mind.

As part of her program, my daughter is doing a basic literacy and numeracy course at a local vocational education provider. It’s tricky targeting her level of understanding but we’re starting to get there. The latest tasks she was set were based around the very useful, practical and necessary skill of shopping on a budget.

She was given eight different retailers, eight different amounts of money to spend, and told to spend this money buying 5 to 6 items at each different shop. Here are the instructions for Bunnings:

“You have $200 to spend at Bunnings.

You need to spend as much of the money as you can, buying 5 different items.

Write down the items you bought and how much each one cost, and then add them up to show the total.”

Seems simple enough, doesn’t it. In fact, it’s deceptively difficult for someone with autism. And it’s extremely time-consuming as an online task. The middle sentence is the killer, so I’m breaking it down:

Making choices, with appropriate support

Making choices can be agonising for autistic people. Even neurotypical people can find choosing difficult. Have you ever found it hard to pick a dish from a menu? Choose a new book to read? A new item of clothing to wear? Chances are, it’s easier when someone else has curated the items for you. Maybe you go with the chef’s choice, the bookshop’s Top 10 reads, choose a top similar to one your friend bought.

These are simple forms of support, helping you in the decision-making process.

Now, extrapolate this to that shopping trip to Bunnings. Ah, Bunnings. That ubiquitous, sprawling, everything-under-the-sun home centre. The task was abstract and open-ended. So, where to start?

My daughter needed to look at an online catalogue, so there was no flipping through a paper catalogue. Frankly, that would have been much easier and faster. Having said that, it is good for her to learn how to find things online. As we began the task, we also discovered how much more information is available online than on paper. That made catalogue browsing even more challenging than flipping through a paper catalogue – an already curated selection of items.

She found the Bunnings site. Then I suggested she choose five out of the fifteen store sections to shop from, and choose one item from each, thus making up her five items. Already, I was instinctively scaffolding the task by curating for her.

- First we went to the garden section, with twelve available categories.

- This led to a second stage of choices: choosing one of the twelve categories. She decided she wanted to look at planter pots and baskets.

- Within the planter pots and baskets were nine more subsections to choose from. This brought her to the third stage of choices. She chose the indoor planter pots.

- This finally brought her to the fourth stage, where she had specific items to look at. *Phew.* Nearly there. But wait – there’s more! Guess what – there was nothing she wanted to buy in this category.

So, we were back to square one, and doing the whole thing again, in a different section of the garden catalogue.

Remember, she had five different items to choose to add up to $200. So, as well as making a choice, she needed to be thinking about the cost. She hadn’t even made the first choice yet, and the process I’ve just outlined had already taken nearly 10 minutes.

Can you imagine how mentally fatiguing that must be? Honestly, I can’t.

It has to be meaningful

Now to the second element which created difficulty. A neurotypical person like me might just be inclined to go, Oh, I’ll buy any old thing, just as long as I find five different things that add up to $200. It’s not like I’m really buying stuff.

Not my daughter.

One of the ways her autistic mind works is that her choices need to have meaning. Fair enough. I’ve seen this in my Aspy boys, who really struggle with hypotheticals. My daughter needed to find things she wanted to buy. She didn’t want to buy any of the plant pots on offer. Again, fair enough, but this adds a layer of complexity to the task, not to mention a significant amount of time.

Did the person who set the task realise this? I wonder.

The tools shouldn’t let you down

Final annoyance – the computer wasn’t properly displaying the search bars within the Bunnings catalogue. It shrank them to almost nothing, making them hard to see and consequently hard to use. This failure in the technology made it hard enough for me to navigate my way through the screens, and completely impossible for my daughter.

I tried not to let my frustration show. This would have only created anxiety for my daughter, who was already finding the task difficult enough. Not for the first time, I found myself wishing for a good old paper catalogue.

This task was designed for special needs students to complete independently, to consolidate and extend their skills in shopping and budgeting. The underlying assumptions about technology exposed another failure to scaffold the task properly. It’s in the same dismissive realm of ‘Get the app’ and ‘Look it up on our website’ advice that often baffles and confuses. The frustration and anxiety this could cause would understandably lead to people to just give up altogether.

In the end, this one, hypothetical shop took us over 40 minutes to complete. No way could my girl have done this independently. My support was needed. The task needed a lot more scaffolding. More “breaking up” into different elements.

Handling the unexpected

The shop at Harvey Norman was similarly difficult, because of the vast catalogue and huge range of things to choose from. The Harvey Norman complication was: the first few items my daughter looked at had no price. You could only find out on request. A learning experience, certainly, but more lost time also.

Short, targeted and almost relevant

Aldi lived up to it’s “Good, different” moniker. “Shopping on a budget” proved to be the best and most relevant task.

My daughter had $20 to spend in the Super Saver’s catalogue, buying five different items and spending as much of her $20 as possible.

This catalogue had just 8 different items in it. Almost all were visible on a single screen.

Tick.

The only hiccup came when she had chosen four items and still had $7 left to spend. Two of the remaining items were too expensive to buy. The last – “Spiced chicken drumsticks” – she didn’t want, because they were spicy.

I urged her unsuccessfully to “pretend”. Then I suggested she buy them for me. Finally, I resorted to subterfuge.

“Maybe they really mean salty, not spicy,” I said, knowing that she loves salty food.

She laughed at this and said, “They made a typo!”

“Well…” I demurred. But it was enough to get her over the line. She chose her final item, satisfied that she’d like to eat it, and completed the task.

The task has to be appropriately scaffolded

It didn’t seem to me that the person who set these tasks had scaffolded them appropriately for the students in this particular class. These young adults all have an intellectual disability, and at least one (my daughter) has autism.

Even though shopping on a budget is a really, really important skill to develop – in fact, ESPECIALLY because it’s a really important skill to develop – I believe vital things were absent:

- Firstly, a foundational understanding that the process of selecting things from an online catalogue is inherently extremely time-consuming.

- Secondly, insufficiently detailed instructions. Yes, the open-ended nature provided freedom of choice, but even a little scaffolding – guidance – would have made a difference.

Here’s a small example:

|

How to order |

2. Supermarket

|

- Thirdly, the writer could have provided some scaffolding by stating the purpose of the shop. This is basic good sense, because (unless it’s shopping “therapy”) we shop for a purpose. Do you go to the supermarket just to faff around and get whatever?

Another small example:

| Why you’re shopping |

You’re planting a veggie garden and you need seedlings and tools. 2. Supermarket You’re making dinner and you need to get food and equipment. |

With my daughter’s tasks, I think the overarching purpose was to practise:

- life skills “making a choice”; and

- numeracy “adding up to a certain amount”.

In the end, she managed the Coles shop by buying what she needed for one of her favourite dinners. However, she needed to double up on some of the ingredients, so she could get close to fulfilling the instruction “spend as much money as possible”. And because she was adamant in her choice of products.

And the moral of the story is…

If you’re setting a task for someone, whether they have autism or not, just stop and consider whether you’re setting it out clearly, with adequate directions/focus and appropriate scaffolding.

Perhaps English is not their first language.

Perhaps they don’t have your technical know-how and experience.

Perhaps you haven’t even fleshed out what they’re expected to do.

What you assumed was a simple task might turn out to be a lot more complex. Not to mention time-consuming, and mentally fatiguing.

Instead, identify the main purpose of the task and try to put yourself in the shoes of your ‘tasker’. Make sure the task is clear, and the steps to achieve it are appropriately scaffolded.

Do a practice run, too.

Like any building, the more we can appropriately scaffold our dependents’ learning – be they young or old – the more confidently and capably they will achieve. Perhaps even, one day, we’ll be able to reduce or even remove some of those supports.

Until next time, stay safe, soap on and Happy Wombatting!